- HOME >

- History of Nihombashi >

- The story of Edo culture ・・・

The story of Edo culture is told by the times – the main figures switch from the samurai to the merchants

Edo-zu Byobu (Folding Screens of the Scenery of Edo) (seventeenth century)

The population of Edo reached a million people by the early eighteenth century. About half of them were members of the warrior class and the rest were ordinary townspeople. These hundreds of thousands of members of the warrior class consisted of retainers of the Shogunate, daimyos and their families of 270 to 280 clans across the country, and retainers that served in the homes of the daimyos in Edo.

Edo in the seventeenth century

The Edo culture of the seventeenth century completely reveals what reflected the social rules, economic power, and tastes of these samurais. First, there are the magnificent structures such as Edo Castle, the daimyo homes, and the Shogun family temples of Kaneiji Temple and Zojoji Temple, which are depicted in the “Edo-zu Byobu” (Folding Screens of the Scenery of Edo). The interiors of structures such as the castle and daimyo homes were decorated with paintings on paper sliding doors and screens made by exclusive painters. Spacious samurai homes had gardens, with some remaining such as the Hama-rikyu Gardens, Korakuen, and, Rikugien. Art forms such as Nogaku theater and the tea ceremony were also practiced quite frequently. Patrons of the Yoshiwara red-light district were mostly warrior-class people such as daimyos, as well as wealthy merchants.

The economic strength of the samurais was gradually diminishing by the eighteenth century, and it was the wealthy merchants that started to play a central role in Edo culture. The Nihombashi area was where many of them chose to live. The fish wholesalers of the Uogashi, drapers of Honcho, and moneylenders of Ryogaecho as well as the merchants who traded products such as lumber, kudarizake (sake from Kansai), oil, medicine, and dried fish created a new culture through lifestyles and interests as they entertained samurais and gathered with their associates.

Women of Edo in the eighteenth century

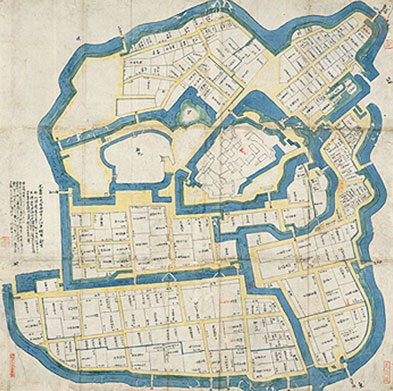

Map of Districts in Edo (around 1830 – 1847)

Spectators gathered in Fukiyacho and Sakaicho in Nihombashi from early morning to see the many performances that were given there like Kabuki plays and puppet shows with storylines that resonated with the townspeople. Among them were those who even competed with each other in investing much money on authors and actors. Haiku, kyoka, and senryu poetry were a popular part of the culture of self-expression. There were even those who became haiku, kyoka, etc. poets on their own. Furthermore, some made business ventures by investing in publishers or by introducing woodblock prints to the world upon starting their own publishing businesses. The demand for women’s goods such as ornamental hairpins and essential items for men such as pocketbooks and tobacco pouches led to the improvement of the craftsmen’s skills; establishing whole new genres in the unique Edo culture. The appearance of exquisite restaurants frequented by wealthy townspeople also developed the food culture of Edo.

The townscape of Edo

By the nineteenth century, the popularization of Edo culture had progressed so far that the demand for woodblock prints and book-lending services had spread among the middle- and lower-class townspeople. The soba shops, shops serving prepared dishes (izakayas), sushi stands, and comical storytelling as well as entertainment such as the theatrical shows and spectacles at the Ryogoku Hirokoji depicted in the “Edo Meisho Zue” (Guide to Famous Edo Site) are also some major examples. The Edo-Tokyo Museum in Ryogoku has a full-size model of the Nihombashi Bridge and holds regular exhibitions of various items surrounding Edo culture.

The Edo-Tokyo Museum http://www.edo-tokyo-museum.or.jp/english/