- HOME >

- History of Nihombashi >

- The people, objects, and ・・・

The people, objects, and information associated with Nihombashi that make your stroll through town more interesting

Anjin Miura

Born William Adams (1564 – 1620). He is the first English person ever to come to Japan. In 1600, he drifted to Bungo (now Oita Prefecture in Kyushu) when piloting the Liefde as part of an expedition team from Holland to the East. Together with Jan Joosten, he met with Ieyasu Tokugawa and served as an advisor in foreign relations and gunnery. Since then, he became a hatamoto (a direct retainer of the shogun) and was granted a townhouse in Anjincho (now Nihombashi Muromachi) in Edo as well as a fief in Miura, Sagami. Therefore, his Japanese name was Anjin Miura. He then married the daughter of a wealthy merchant of Nihombashi and had two children. He served at a British trading post that was established in Hirado of Nagasaki Prefecture, but passed away in 1620 without ever having gone back to England. A monument stands at the location of his former residence in Nihombashi’s Anjincho, which was named after him.

Yan Yosu (Jan Joosten)

Born Jan Joosten van Loodensteyn (1556? – 1623). After drifting to Kyushu on the Dutch ship, the “Liefde” with William Adams, he became involved in foreign relations and trade under Ieyasu Tokugawa. He was granted a house within the inner moat of Edo Castle and later married a Japanese woman. He chartered Red Seal Ships while conducting trade in Southeastern Asia, but drowned to death when his ship sank. The area around his home in Edo was named Yaesugashi after him, and the name is still carried on at Yaesu near Tokyo Station.

Basho Matsuo

A representative haiku poet of Japan and is known worldwide (1644 – 1694). In 1672, at the age of twenty-nine, he went to Edo and stayed at the home of the official carp wholesaler, Kensui Sugiyama (commonly known as “Koiya”) in Nihombashi Honodawaracho (now Nihombashi 1-Chome / Muromachi 1-Chome). After interacting and training with other poets in Edo, he received the rank of “sosho” (a professional haiku poet) in 1678. In 1680, he relocated to a hermitage that was a remodeled hut for watchmen of a carp cage owned by a carp dealer. This hermitage was called “Hakusendo” but was renamed “Bashoan” in 1681 as a basho (Japanese banana) that was planted there grew so well. This was when he decided to take the pen name “Basho”.

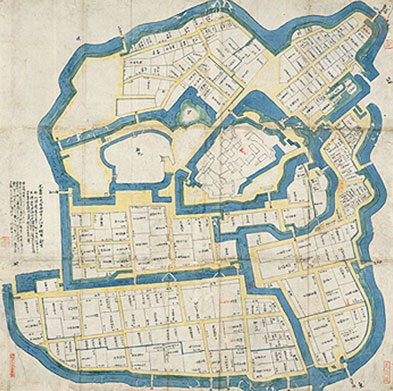

The Nihombashi Bridge and its placard spot

Because the original Nihombashi Bridge that was built in 1603 was at the center of urban Edo, it burned down every time there was a great fire. It was completely or partially burned down 10 times and had to be restored 12 times during the Edo period due to damages or aging. Records from 1806 show that the bridge was 51 meters in length, 7.8 meters in width, had a pile structure of eight rows with three columns each, and was built with durable wood that could be cut precisely such as white zelkova. A placard spot that announced important ordinances and proclamations was placed at the southern end. On the other side of the placard spot was where major criminals such as those who have murdered their masters, those who have attempted double suicide, and monks who have committed sexual offenses were punished to set an example to other criminals.

Toki-no-Kane Bell Tower

A time bell that was first installed in Edo’s Nihombashi Honkokucho in 1626. A bell tower was installed in the home of Genshichi Tsuji, who came from a line of bell ringers for Edo Castle. After that, another bell tower was built in an open space of about 39 square meters behind his home in 1700 as the area grew crowded with structures belonging to tradesmen. The income of the bell ringers was a fixed amount of money collected from 410 home owners. Today, the “Toki-no-Kane Bell Tower”, which was built in 1711, stands at Jisshi Park in Nihombashi Kodenmacho 1-Chome.

Nagasakiya

Genemon Nagasakiya moved to Honkokucho 3-Chome from Nagasaki during the early Edo period and started a medicine business. As of 1609, his place of business was where Dutch traders stayed when visiting the feudal government in thanks for permission to conduct trade in Nagasaki. The residence was of a two-storied formal honjin-style structure. Red, white, and blue curtains were hung when the Dutch traders stayed. In 1858, it became a specified shop for foreign books. It was called “the Dejima of Edo” and was a valued place where one could interact with Western culture in Edo. Today, an explanation board of the Nagasakiya remains is posted beside Shin-Nihombashi Station at Muromachi 4-Chome.

Shibaicho Ruins

Of the three major Kabuki theaters of Edo, the Ichimura-za and Nakamura-za were located in Nihombashi’s Fukiyacho and Sakaicho (now Ningyocho). This area was also called Shibaicho (“the town of theater”) as it was lined with huts that provided entertainment such as minor theater and joruri puppet shows. Shibaicho also had teahouses for enjoying theater as well as restaurants and other eating establishments, knickknack shops, and illustrated storybook shops, which were crowded with visitors from opening time at around six in the morning until about five in the evening. There is an explanation board for the Shibaicho ruins at the old sites of these establishments (now Nihombashi Ningyocho 3-Chome 2 to 7). The Nakamura-za stood in the southern part of Nakabashi, which was located between Nihombashi and Kyobashi, until it was relocated to Nihombashi in 1632, but there is a “Birthplace of Edo Kabuki” monument at its old site (current address: 3-4, Kyobashi, Chuo-ku).

Fukutoku Shrine

Inari Shrine is said to have been founded around the late ninth century; seven hundred years before the Edo period. An annual celebration is held every May 9th. The shrine records state that the grounds specified by the second Tokugawa shogun, Hidetada, were a little more than 1,100 square meters in area during his reign, but got significantly smaller as they were taken over by the land reserved for the merchants nearby. The area used to be called Fukutokumura, and it is said that this is how the shrine got its name. It was a place of worship for shogun Ieyasu Tokugawa, the second Tokugawa shogun, Hidetada, and other important figures.

Mitsui Memorial Museum

The Mitsui Library Annex was established to preserve and exhibit important cultural assets passed down from the Mitsui conglomerate, which was founded by Takatoshi Mitsui of Echigoya in the late seventeenth century. The exhibits include “Sessho-zu” (Pine Trees in Snow), which was drawn for the Mitsui Family by the renown painter Okyo Maruyama as well as swords – two of which are national treasures, and Noh masks passed on by the Ukyo Kongo Family of Nogaku theater. There is also a collection of teaware, a collection of some of the world’s finest philatelic items, and more.

http://www.mitsui-museum.jp/english/english.html

Bank of Japan CURRENCY MUSEUM

Here, visitors can see the history of currency as actual Japanese currency from the Edo period is on display as well as that from all ages and cultures. Admission is free.

http://www.imes.boj.or.jp/cm/english/

Ozu History Museum

A museum dedicated to the Ozu paper wholesaler founded in Nihombashi Odenmacho by a paper merchant from Ise in the mid-seventeenth century. On display here are antique writings from the Edo period, historical business documents, and images created after the modernization of Japan.

http://www.ozuwashi.net/english

The Edo-Tokyo Museum

A museum that exhibits and explains historic documents and items that introduce the history and culture of Edo and Tokyo. It is highly recommended for those who want a deeper understanding of Edo culture.

http://www.edo-tokyo-museum.or.jp/english/

Fukagawa Edo Museum

The perfect museum for getting to know the lifestyles of the common people of Edo. “Nagaya” tenements, which were typical dwelling places of the common people, as well as their living environments have been replicated for visitors to enjoy.

http://www.kcf.or.jp/fukagawa/